Risk & Vulnerability

|

|

|

|

Vulnerability assessment is the analysis of the expected impacts, risks and the adaptive capacity of a region or sector to the effects of climate change. Vulnerability assessment encompasses more than simple measurement of the potential harm caused by events resulting from climate change: it includes an assessment of the region's or sector's ability to adapt. The term vulnerability is used differently in the climate change context. We define vulnerability to climate change broadly as follows: "The propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected. Vulnerability encompasses a variety of concepts including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope and adapt".

There are different ways in which vulnerability and risk can be defined and analysed. In climate change publications, vulnerability is often defined as a function of the character, magnitude, and rate of climate variation and change to which a system is exposed, together with its sensitivity and adaptive capacity. Humans can increase their vulnerability by urbanisation of coastal flood plains, by deforestation of hill slopes or by constructing buildings in risk-prone areas. Publications in other areas, such as those relating to natural hazards, tend to define vulnerability as an inherent characteristic of a social system or societal group.

A common means of measurement of the risk of a natural hazard is as follows:

Risk of the hazard = Expected damage of the hazard x Probability of the hazard occurring.

There are three dimensions of vulnerability to climate change: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

The expression “things they value” not only refers to economic value and wealth, but also to places and to cultural, spiritual, and personal values. In addition, this expression refers to critical physical and social infrastructure, including such physical infrastructure as police, emergency, and health services buildings, communication and transportation networks, public utilities, and schools and daycare centers, and such social infrastructure as extended families, neighborhood watch groups, fraternal organizations, and more. The expression even refers to such factors as economic growth rates and economic vitality. People value some places and things for intrinsic reasons and some because they need them to function successfully in our society.

Some people and the things they value can be highly vulnerable to low-impact climate changes because of high sensitivity or low adaptive capacity, while others can have little vulnerability to even high-impact climate changes because of insensitivity or high adaptive capacity. Climate change will result in highly variable impact patterns because of these variations in vulnerability in time and space.

Some groups of people are inherently more vulnerable to climate change than others. The very old or very young, the sick, and the physically or mentally challenged are vulnerable. Disadvantaged groups, such as minorities, those with few educational opportunities, or non-English speakers are more vulnerable than the majority, better-educated, English-speaking population. Women, who typically spend more time and effort on care-giving to parents, children, and the sick than men do, are more vulnerable because that care-giving exposes them more to the impacts of climate change. More vulnerable groups often combine these categories, such as the poor—who can be old, minority, non-English speaking, and female, for example. Another example of a particularly vulnerable group is the single-mother household, which can be headed by a poor woman of color who is responsible not only for caregiving, but also for providing the family income.

There are different ways in which vulnerability and risk can be defined and analysed. In climate change publications, vulnerability is often defined as a function of the character, magnitude, and rate of climate variation and change to which a system is exposed, together with its sensitivity and adaptive capacity. Humans can increase their vulnerability by urbanisation of coastal flood plains, by deforestation of hill slopes or by constructing buildings in risk-prone areas. Publications in other areas, such as those relating to natural hazards, tend to define vulnerability as an inherent characteristic of a social system or societal group.

A common means of measurement of the risk of a natural hazard is as follows:

Risk of the hazard = Expected damage of the hazard x Probability of the hazard occurring.

There are three dimensions of vulnerability to climate change: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

- Exposure is the degree to which people and the things they value could be exposed to climate variation or change;

- sensitivity is the degree to which they could be harmed by that exposure; and

- adaptive capacity is the degree to which they could mitigate the potential for harm by taking action to reduce exposure or sensitivity.

The expression “things they value” not only refers to economic value and wealth, but also to places and to cultural, spiritual, and personal values. In addition, this expression refers to critical physical and social infrastructure, including such physical infrastructure as police, emergency, and health services buildings, communication and transportation networks, public utilities, and schools and daycare centers, and such social infrastructure as extended families, neighborhood watch groups, fraternal organizations, and more. The expression even refers to such factors as economic growth rates and economic vitality. People value some places and things for intrinsic reasons and some because they need them to function successfully in our society.

Some people and the things they value can be highly vulnerable to low-impact climate changes because of high sensitivity or low adaptive capacity, while others can have little vulnerability to even high-impact climate changes because of insensitivity or high adaptive capacity. Climate change will result in highly variable impact patterns because of these variations in vulnerability in time and space.

Some groups of people are inherently more vulnerable to climate change than others. The very old or very young, the sick, and the physically or mentally challenged are vulnerable. Disadvantaged groups, such as minorities, those with few educational opportunities, or non-English speakers are more vulnerable than the majority, better-educated, English-speaking population. Women, who typically spend more time and effort on care-giving to parents, children, and the sick than men do, are more vulnerable because that care-giving exposes them more to the impacts of climate change. More vulnerable groups often combine these categories, such as the poor—who can be old, minority, non-English speaking, and female, for example. Another example of a particularly vulnerable group is the single-mother household, which can be headed by a poor woman of color who is responsible not only for caregiving, but also for providing the family income.

|

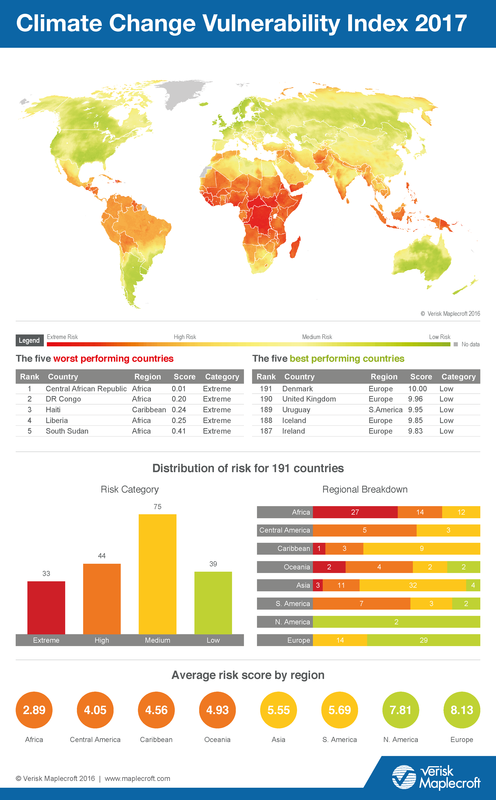

Risk is any factor that exposes people to danger or impedes (or threatens to impede) people achieving their goals. Risk can also be viewed as a motivation to make changes that find new solutions. If risk and vulnerability are to be addressed, they must first be identified, assessed and quantified. One way of measuring the risk of climate change is the Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI) that was developed by Maplecroft, a consultancy firm that specialises in identifying global risks. The CCVI is a composite indicator that combines three simpler composite indices:

Codrington, Stephen. Our Changing Planet (Planet Geography Book 1) (Kindle Locations 6581-6588). Solid Star Press. Kindle Edition. |

| Impacts associated with climate change variables | |

| File Size: | 45 kb |

| File Type: | |

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| vulnerability.docx | |

| File Size: | 151 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

Risk Perception

Risk can be very personal and is influenced by:

What factors influence our risk perception?

Risk can be very personal and is influenced by:

- Experience: If you have dealt with the hazard before your perception of risk can either increase or decrease depending on your now more informed view.

- Material well being: Wealth provides you with more choices and potential more protection to certain hazards.

- Personality: Are you an adrenaline junkie or do you get scared of the dark?

What factors influence our risk perception?

- Is the risk voluntary? Professional soldiers for example will perceive the risk of being shot differently from a civilian.

- Time scale: people perceive immediate impacts of a hazard as more severe and 'real' than long term ones. In an earthquake for example the risk of a building falling on you is more feared than the long term risk to your health.

- Psychological perception: certain hazards create a very intense fear response in humans for example the fear of fire and any hazard that might cause this will be perceived as worse than say an avalanche.

- Understanding/Knowledge: We fear what we do not know much about or we fear it less due to a limited understanding of the true risk.

- Media: Certain hazards are widely publicized and covered in the international media. This can colour our perception of risk.

- What is Vulnerability and Risk?

- What factors are included when calculating the CCVI?

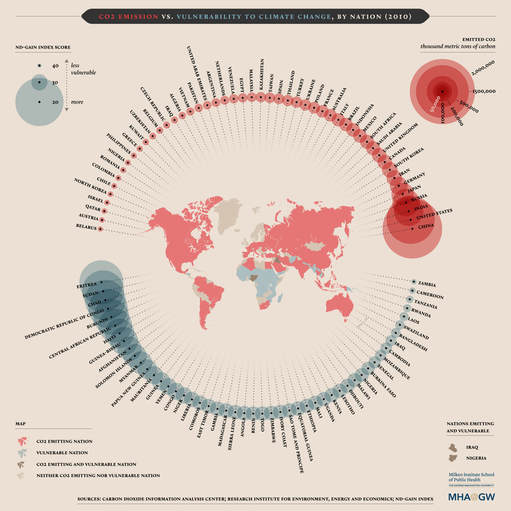

- Describe the world pattern of climate change risk as indicated by the CCVI.

- Compare the vulnerability to climate change in the eight regions shown.

- Explain why vulnerability and readiness work in opposite directions when assessing climate change risk.

- Explain why each of the following groups are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change: (a) impoverished people, (b) women, (c) children, (d) poorly educated people, (e) the elderly.

- What factors affect the strength of a person’s risk perception about climate change?

- What is resilience?

- Essay: Explain why there are differences in Vulnerability and Risk?

Contrasting vulnerabilities

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| Impacts Vulnerabilities and Adaptations in Developing Countries | |

| File Size: | 3275 kb |

| File Type: | |

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| Vulnerability to Climate Change in European Regions | |

| File Size: | 416 kb |

| File Type: | |

Extended Reading - Full Report on Impacts and Vulnerabilities in Europe

| Climate Change Impacts and vulnerabilities | |

| File Size: | 67412 kb |

| File Type: | |

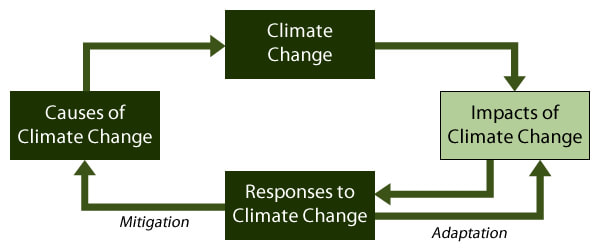

Adaptation & Mitigation

Because we are already committed to some level of climate change, responding to climate change involves a two-pronged approach:

- Reducing emissions of and stabilizing the levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (“mitigation”). Refers to the policies which are meant to delay, reduce or prevent climate changes - cutting C02 emissions by instituting congestion charges or carbon sinks.

- Adapting to the climate change already in the pipeline (“adaptation”). Refers to the policies which are designed to reduce the existing impacts of climate change - flood protection and coastal erosion.

Mitigation – reducing climate change – involves reducing the flow of heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, either by reducing sources of these gases (for example, the burning of fossil fuels for electricity, heat or transport) or enhancing the “sinks” that accumulate and store these gases (such as the oceans, forests and soil). The goal of mitigation is to avoid significant human interference with the climate system, and “stabilize greenhouse gas levels in a timeframe sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner” (from the 2014 report on Mitigation of Climate Change from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, page 4).

Adaptation – adapting to life in a changing climate – involves adjusting to actual or expected future climate. The goal is to reduce our vulnerability to the harmful effects of climate change (like sea-level encroachment, more intense extreme weather events or food insecurity). It also encompasses making the most of any potential beneficial opportunities associated with climate change (for example, longer growing seasons or increased yields in some regions).

Throughout history, people and societies have adjusted to and coped with changes in climate and extremes with varying degrees of success. Climate change (drought in particular) has been at least partly responsible for the rise and fall of civilizations. Earth’s climate has been relatively stable for the past 12,000 years and this stability has been crucial for the development of our modern civilization and life as we know it. Modern life is tailored to the stable climate we have become accustomed to. As our climate changes, we will have to learn to adapt. The faster the climate changes, the harder it could be.

While climate change is a global issue, it is felt on a local scale. Cities and municipalities are therefore at the frontline of adaptation. In the absence of national or international climate policy direction, cities and local communities around the world have been focusing on solving their own climate problems. They are working to build flood defenses, plan for heatwaves and higher temperatures, install water-permeable pavements to better deal with floods and stormwater and improve water storage and use.

According to the 2014 report on Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability(page 8) from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, governments at various levels are also getting better at adaptation. Climate change is starting to be factored into a variety of development plans: how to manage the increasingly extreme disasters we are seeing and their associated risks, how to protect coastlines and deal with sea-level encroachment, how to best manage land and forests, how to deal with and plan for reduced water availability, how to develop resilient crop varieties and how to protect energy and public infrastructure.

Climate change mitigation and adaptation are not mutually exclusive but are key partners in any strategy to combat climate change. As effective mitigation can restrict climate change and its impacts, it can also reduce the level of adaptation required by communities and nations.

However, there is a significant time lag between mitigation activities and their effects on climate change reduction. Even if we were to dramatically reduce emissions today, current greenhouse gases in the atmosphere would continue to result in global warming and drive climate change for many decades. And so, it would also be many decades before adaptation requirements are reduced.

Adaptation – adapting to life in a changing climate – involves adjusting to actual or expected future climate. The goal is to reduce our vulnerability to the harmful effects of climate change (like sea-level encroachment, more intense extreme weather events or food insecurity). It also encompasses making the most of any potential beneficial opportunities associated with climate change (for example, longer growing seasons or increased yields in some regions).

Throughout history, people and societies have adjusted to and coped with changes in climate and extremes with varying degrees of success. Climate change (drought in particular) has been at least partly responsible for the rise and fall of civilizations. Earth’s climate has been relatively stable for the past 12,000 years and this stability has been crucial for the development of our modern civilization and life as we know it. Modern life is tailored to the stable climate we have become accustomed to. As our climate changes, we will have to learn to adapt. The faster the climate changes, the harder it could be.

While climate change is a global issue, it is felt on a local scale. Cities and municipalities are therefore at the frontline of adaptation. In the absence of national or international climate policy direction, cities and local communities around the world have been focusing on solving their own climate problems. They are working to build flood defenses, plan for heatwaves and higher temperatures, install water-permeable pavements to better deal with floods and stormwater and improve water storage and use.

According to the 2014 report on Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability(page 8) from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, governments at various levels are also getting better at adaptation. Climate change is starting to be factored into a variety of development plans: how to manage the increasingly extreme disasters we are seeing and their associated risks, how to protect coastlines and deal with sea-level encroachment, how to best manage land and forests, how to deal with and plan for reduced water availability, how to develop resilient crop varieties and how to protect energy and public infrastructure.

Climate change mitigation and adaptation are not mutually exclusive but are key partners in any strategy to combat climate change. As effective mitigation can restrict climate change and its impacts, it can also reduce the level of adaptation required by communities and nations.

However, there is a significant time lag between mitigation activities and their effects on climate change reduction. Even if we were to dramatically reduce emissions today, current greenhouse gases in the atmosphere would continue to result in global warming and drive climate change for many decades. And so, it would also be many decades before adaptation requirements are reduced.

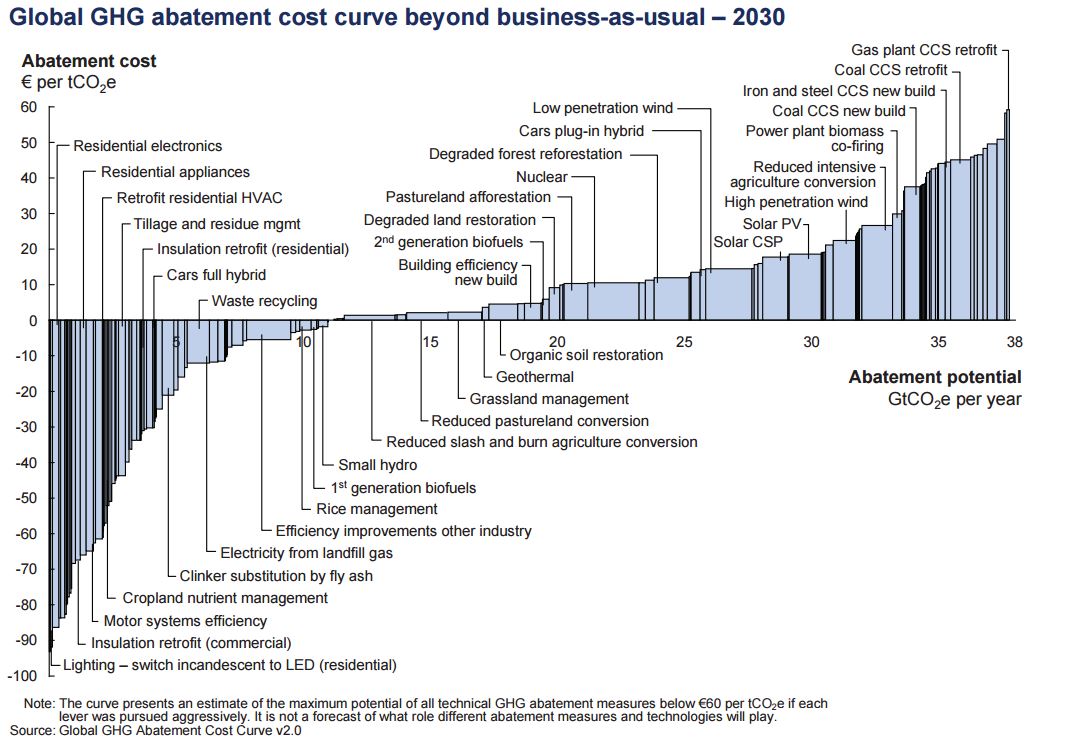

'Abatement potential' is the term we use to describe the magnitude of potential GHG reductions which could be technologically and economically feasible to achieve. We measure this in tonnes (or thousand/million/billion tonnes) of greenhouse gases (which is abbreviated as carbon dioxide equivalents, or CO2e). Note that our measure of CO2e includes all greenhouse gases, not just CO2.2 So, on the x-axis we have the abatement potential of our range of options for reducing our GHG emissions; here, each bar represents a specific technology or practice.3 The thicker the bar, the greater its potential for reducing emissions.

On the y-axis we have the abatement cost. This measures the cost of reducing our GHG emissions by one tonne by the year 2030, and in this case is given in € (i.e. € per tonne of CO2e saved).4 But it's important to clarify here what we mean by the term 'cost'. 'Cost' refers to the economic impact (which can be a loss or gain) of investing in a new technology rather than continuing with 'business-as-usual' technologies or policies. To do this, we first have to assume a 'baseline' of what we expect 'business-as-usual' policies and investments would be. This is done—for both costs and abatement potential—based on a combination of empirical evidence, energy models, and expert opinion.5 This can, of course, be challenging to do; the need to make long-term predictions/projections in this case is an important disadvantage to cost-abatement curves. Whilst not perfect, it does provide useful estimates of relative costs and abatement potential.

On the y-axis we have the abatement cost. This measures the cost of reducing our GHG emissions by one tonne by the year 2030, and in this case is given in € (i.e. € per tonne of CO2e saved).4 But it's important to clarify here what we mean by the term 'cost'. 'Cost' refers to the economic impact (which can be a loss or gain) of investing in a new technology rather than continuing with 'business-as-usual' technologies or policies. To do this, we first have to assume a 'baseline' of what we expect 'business-as-usual' policies and investments would be. This is done—for both costs and abatement potential—based on a combination of empirical evidence, energy models, and expert opinion.5 This can, of course, be challenging to do; the need to make long-term predictions/projections in this case is an important disadvantage to cost-abatement curves. Whilst not perfect, it does provide useful estimates of relative costs and abatement potential.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| synergies_between_adaptation_and_mitigation_in_a_nutshell.pdf | |

| File Size: | 804 kb |

| File Type: | |

|

|

|

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| Large Scale Action on Climate Change | |

| File Size: | 163 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

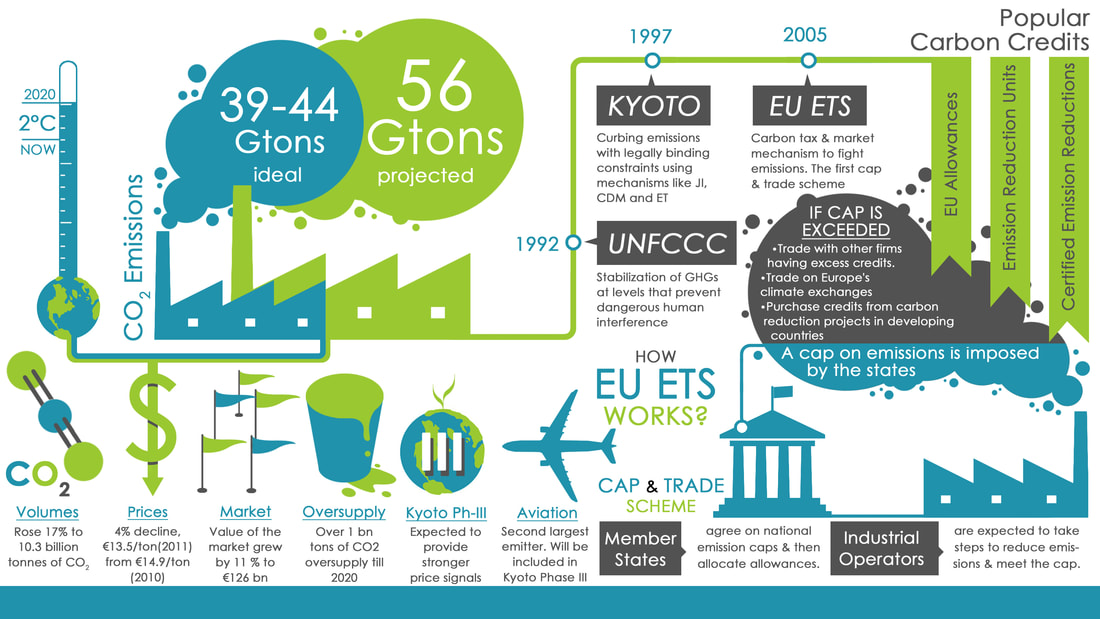

Carbon emissions offsetting and trading

What is the difference between carbon offsetting and trading?

A carbon credit is an instrument that represents ownership of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that can be traded, sold, retired, etc. If a company is regulated under a cap-and-trade system, they most likely have an allowance of credits they can use toward their cap. If they use fewer emissions (credits) than they are allocated, they can trade, sell, hold, or do whatever they like with the credit. If it is sold, it is their allowance of emissions being sold to someone else. (Likewise, if they use more than they have allocated, they must purchase a credit to be in compliance). So a credit becomes tradable, like an offset, because of a very real reduction in emissions, but often times the reduction is from an activity you may not have thought of, like changing a business practice, flying less, turning off equipment at night, and so on.

A carbon offset, on the other hand, is also a very real reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, and results in the generation of a carbon credit, but from a project with clear boundaries, title, project documents and a verification plan. Carbon offsets generate reductions outside the ‘four walls’ of a company in most cases. Projects like building a wind farm, supporting truck stop electrification projects, planting trees or preserving forests are very common carbon offset projects. These reductions occur outside the companies’ four walls but more importantly, outside any regulatory requirement. They are in addition to what is being mandated.

So a carbon offset derived from a third-party certified project usually generates a carbon credit. But a carbon credit need not be from a carbon offset project. Because carbon dioxide is a global impact gas, meaning it does not affect us locally through increased smog or acid rain, both offsets and credits have the exact same reduction in carbon dioxide emissions and have the exact same benefit to the planet in terms of climate change.

A carbon credit is an instrument that represents ownership of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that can be traded, sold, retired, etc. If a company is regulated under a cap-and-trade system, they most likely have an allowance of credits they can use toward their cap. If they use fewer emissions (credits) than they are allocated, they can trade, sell, hold, or do whatever they like with the credit. If it is sold, it is their allowance of emissions being sold to someone else. (Likewise, if they use more than they have allocated, they must purchase a credit to be in compliance). So a credit becomes tradable, like an offset, because of a very real reduction in emissions, but often times the reduction is from an activity you may not have thought of, like changing a business practice, flying less, turning off equipment at night, and so on.

A carbon offset, on the other hand, is also a very real reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, and results in the generation of a carbon credit, but from a project with clear boundaries, title, project documents and a verification plan. Carbon offsets generate reductions outside the ‘four walls’ of a company in most cases. Projects like building a wind farm, supporting truck stop electrification projects, planting trees or preserving forests are very common carbon offset projects. These reductions occur outside the companies’ four walls but more importantly, outside any regulatory requirement. They are in addition to what is being mandated.

So a carbon offset derived from a third-party certified project usually generates a carbon credit. But a carbon credit need not be from a carbon offset project. Because carbon dioxide is a global impact gas, meaning it does not affect us locally through increased smog or acid rain, both offsets and credits have the exact same reduction in carbon dioxide emissions and have the exact same benefit to the planet in terms of climate change.

What motivates companies to engage in voluntary carbon markets?

The reasons are diverse:

• Fulfilling voluntary corporate GHG reduction targets, especially when internal reductions are not feasible or cost-effective;

• Creating internal incentives for reductions by internalizing the cost of carbon and putting real financial pressure on managers;

• Gaining carbon market experience in order to increase authority and influence in policy discussions about climate change and GHG regulation;

• Preparing for potential regulatory requirements that may include a range of offset approaches and partnerships;

• Enhancing brands and/or differentiating products, in some cases with the aim of offering products at a price premium;

• Attracting investors, particularly in light of increasing awareness of risks associated with GHG emissions in a carbon-constrained future;

• Enhancing intelligence by creating systems that support learning more about the nuances of the production process and identifying richer input and waste data.

The reasons are diverse:

• Fulfilling voluntary corporate GHG reduction targets, especially when internal reductions are not feasible or cost-effective;

• Creating internal incentives for reductions by internalizing the cost of carbon and putting real financial pressure on managers;

• Gaining carbon market experience in order to increase authority and influence in policy discussions about climate change and GHG regulation;

• Preparing for potential regulatory requirements that may include a range of offset approaches and partnerships;

• Enhancing brands and/or differentiating products, in some cases with the aim of offering products at a price premium;

• Attracting investors, particularly in light of increasing awareness of risks associated with GHG emissions in a carbon-constrained future;

• Enhancing intelligence by creating systems that support learning more about the nuances of the production process and identifying richer input and waste data.

Further links and research of Carbon Offsetting and Trading

Technology and Geo-Engineering

Geo-engineering schemes are projects designed to tackle the effects of climate change directly, usually by removing CO2 from the air or limiting the amount of sunlight reaching the planet's surface. Although large-scale geo-engineering is still at the concept stage, advocates claim that it may eventually become essential if the world wants to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Critics, by contrast, claim that geo-engineering isn't realistic – and may be a distraction from reducing emissions.

The main categories of proposed geoengineering techniques are:

The main categories of proposed geoengineering techniques are:

- SOLAR RADIATION MANAGEMENT: SRM techniques attempt to reflect sunlight back into space, and include a range of ideas, from orbiting mirrors, tonnes of sulphates sprayed into the stratosphere, and modifying clouds, plants and ice to make them more reflect more sunlight.

- CARBON DIOXIDE REMOVAL: These proposals posit that it’s possible to suck carbon out of the atmosphere on a massive scale, using a combination of biological and mechanical methods, from seeding the ocean with iron pellets to create plankton blooms to creating forests of mechanical “artificial trees”.

- EARTH RADIATION MANAGEMENT: ERM proponents suggest that negative effects of climate change can be offset by allowing heat to escape into space – for example, by thinning cirrus clouds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Amity - Biogas

The Amity Foundation, an independent Chinese voluntary organization, was created in 1985 on the initiative of Chinese Christians to promote education, social services, health, and rural development from China’s coastal provinces in the east to the minority areas of the west.

Amity's Purpose & Vision

Abiding by the principle of mutual respect in faith, Amity builds friendship with people at home and abroad. Through the promotion of holistic development and public welfare, Amity serves society, benefits the people, and strives to promote world peace.

In this way, Amity:

- contributes to China’s social development and openness to the outside world,

- makes Christian involvement and participation in meeting the needs of society more widely known to the Chinese people,

- serves as a channel for people-to-people contact and the ecumenical sharing of resources.

Amity's Purpose & Vision

Abiding by the principle of mutual respect in faith, Amity builds friendship with people at home and abroad. Through the promotion of holistic development and public welfare, Amity serves society, benefits the people, and strives to promote world peace.

In this way, Amity:

- contributes to China’s social development and openness to the outside world,

- makes Christian involvement and participation in meeting the needs of society more widely known to the Chinese people,

- serves as a channel for people-to-people contact and the ecumenical sharing of resources.

|

|

|

|

Background

The International biogas program started in 2011, with the aim to transfer biogas technology from China, to Madagascar. The responsible partner in China is Amity Foundation. The Malagasy Lutheran Church (MLC) is the responsible partner in Madagascar. Norwegian Mission Society (NMS) has had a coordination role in the program.

Amity Foundation had been working on biogas system building for poor farmers in China for many years. These projects were very successful, and the idea of an exchange program came up. The project started in October 2011, and continued until 2014. During 2015, the plan is to have a reflection year in Madagascar, to follow-up the evaluation, and make decisions on the future development.

Outcomes of the IBP include

The International biogas program started in 2011, with the aim to transfer biogas technology from China, to Madagascar. The responsible partner in China is Amity Foundation. The Malagasy Lutheran Church (MLC) is the responsible partner in Madagascar. Norwegian Mission Society (NMS) has had a coordination role in the program.

Amity Foundation had been working on biogas system building for poor farmers in China for many years. These projects were very successful, and the idea of an exchange program came up. The project started in October 2011, and continued until 2014. During 2015, the plan is to have a reflection year in Madagascar, to follow-up the evaluation, and make decisions on the future development.

Outcomes of the IBP include

- Technological skills have been transferred from Chinese to MLC’s technicians, as observed in the high quality of digesters in Madagascar.

- In China, the appropriateness of the biogas technology in rural livelihoods is evident from 95% of the digesters built by the IBP being in use.

- Biogas has freed time in the household, particularly noticeable in Madagascar. Training in household economy has enabled people to valorise the time saved.

- Biogas and trainings appears to have had impact on perception of gender roles within the household, particularly in Madagascar. In China improved sanitary conditions, training in health, establishment of women’s development associations, and income generating activities have improved women’s daily lives.

- From the trainings, women have gained ideas on how to improve household income. Some have initiated small entrepreneurial projects following trainings through the IBP in both China and Madagascar.

- Biogas has had an important impact on hygiene in China with improved toilet facilities. Cleanliness and indoor air quality in the kitchen has improved in both countries.

- Biogas has a positive impact on the local environment in both countries. Over time, this will be evident in Madagascar where firewood is very scarce and few alternative energy sources are available.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Climate change: business & Civil Society

Business

Climate change effects on businesses will depend on the nature of the enterprise and the degree of exposure. Businesses with a short-term outlook are more exposed to issues associated with climate variability than climate change (although in the short term they may be affected by climate change adaptation regulation). Others, particularly in the infrastructure related sector or those with longer-term investment horizons are more likely to be exposed to the effects of climate change. The Bangkok floods in 2011 sent ripples of impacts through the Australian private sector supply chain and were a stark reminder about the interconnected risks from a global marketplace. Whether dealing with climate variability or climate change, there are opportunities to adapt and therefore reduce exposure and/or take advantage of opportunities. Impacts from a variable climate can be direct (e.g. flooding of business premises, impacts on workers from heat stress) or indirect (e.g. impact on supply chains or customer bases)

Insurance

At present the commentary from the insurance industry is mixed. Global reinsurers are increasingly recognising their exposure to climate-related risks. Already some insurers have increased premiums and withdrawn from some locations after recent extreme events . As so many organisations transfer their climate-related risks to the insurance industry, any shift in insurance availability and affordability is likely to have cascading effects through the private sector (especially in real estate, property development and lending).

Agriculture and food industries.

A warming climate is likely to affect the potential to grow certain crops in some places, especially if there are changes to the rainfall regime. The industry may be required to make transformational changes to manage these impacts, growing new crops and moving into new locations. This may in turn affect wholesale and retail prices, as well as transport and trading patterns. The impacts along the supply chain will come not only from the Australian farming industry, but also from impacts on global agriculture.

Financial services.

If insurance becomes unavailable or unaffordable in certain locations then the portfolio of a lender may be affected. Responses (e.g. calling in mortgages) may affect asset value and organisational reputation, whereas failing to respond may expose a listed company to shareholder litigation.

Climate change effects on businesses will depend on the nature of the enterprise and the degree of exposure. Businesses with a short-term outlook are more exposed to issues associated with climate variability than climate change (although in the short term they may be affected by climate change adaptation regulation). Others, particularly in the infrastructure related sector or those with longer-term investment horizons are more likely to be exposed to the effects of climate change. The Bangkok floods in 2011 sent ripples of impacts through the Australian private sector supply chain and were a stark reminder about the interconnected risks from a global marketplace. Whether dealing with climate variability or climate change, there are opportunities to adapt and therefore reduce exposure and/or take advantage of opportunities. Impacts from a variable climate can be direct (e.g. flooding of business premises, impacts on workers from heat stress) or indirect (e.g. impact on supply chains or customer bases)

Insurance

At present the commentary from the insurance industry is mixed. Global reinsurers are increasingly recognising their exposure to climate-related risks. Already some insurers have increased premiums and withdrawn from some locations after recent extreme events . As so many organisations transfer their climate-related risks to the insurance industry, any shift in insurance availability and affordability is likely to have cascading effects through the private sector (especially in real estate, property development and lending).

Agriculture and food industries.

A warming climate is likely to affect the potential to grow certain crops in some places, especially if there are changes to the rainfall regime. The industry may be required to make transformational changes to manage these impacts, growing new crops and moving into new locations. This may in turn affect wholesale and retail prices, as well as transport and trading patterns. The impacts along the supply chain will come not only from the Australian farming industry, but also from impacts on global agriculture.

Financial services.

If insurance becomes unavailable or unaffordable in certain locations then the portfolio of a lender may be affected. Responses (e.g. calling in mortgages) may affect asset value and organisational reputation, whereas failing to respond may expose a listed company to shareholder litigation.

For the private sector, adaptation is about three key elements:

- maintaining economic viability;

- managing climate legal risk and responding to adaptation regulations; and

- positioning to identify opportunities.

Civil Society

Civil society is the "aggregate of non-governmental organizations and institutions that manifest interests and will of citizens". Civil society includes the family and the private sphere, referred to as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business.

Civil society is the "aggregate of non-governmental organizations and institutions that manifest interests and will of citizens". Civil society includes the family and the private sphere, referred to as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business.